Breaking news here on Hooch Planet: back in March of this year, the West Virginia state legislature announced that it would be legal for Mountaineers to produce up to 10 gallons of hooch annually for their own consumption. Just a few months later, on July 11th, a US district court judge in northern Texas ruled that the US government’s 156-year-old ban on home distilling is unconstitutional. Judge Mark Pittman found that the ban cannot be justified under interstate commerce rules and does not pose a significant threat to tax revenue. Therefore, he said, the ban "did nothing more than statutorily ferment a crime." Nice one, Mark.

Prior to July’s federal court ruling, West Virginia was the first state to legalize home distilling in the “moonshine belt”—a region demarcated by the New York Times in 1973 as “running through Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina” and including “Virginia, Tennessee, South Carolina, West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Florida, and Texas”. In other words, most of the Deep South and Appalachia.

Moonshine isn’t only a southern phenomenon, but that part of the US has been closely associated with illicit booze since before (and during, and after) prohibition. As I’ve been arguing in this space (hopefully convincingly), making alcohol is a universal activity that happens all around the world at all points in human history using all manner of raw materials and methods. And yet, when West Virginia legalized “moonshine”, the journalists just couldn’t help themselves, as this lede from NPR demonstrates:

We've distilled some news for you about a piece of Appalachian heritage boiled up during West Virginia's latest legislative session.

Oh boy.

I have never lived in West Virginia, but my family does. My brother-in-law is 10th generation (my niece now 11th), and after my father’s death in 2021, my mom moved there from east Tennessee.

Like much of Appalachia and the American South, West Virginia was a reliably blue state up until the Bush/Gore election of 2000. Since then what began as a gradual purpling became a sweeping Republican dominance of state and federal politics. The last time West Virginia went for a democratic presidential candidate was Bill Clinton in 1996.

West Virginia politics have long been a case study in clientelism, with the state apparatus effectively captured by coal and timber interests for pretty much the entirety of its existence. But West Virginia has also always had a rebel streak, including the brave coal miners who went to war with the coal companies and ultimately their own government to fight for the right to organize.

In fact, the very founding of the state—the cleaving of the highlands from Greater Virginia on the eve of the Civil War—is a story of a secessionist movement within a secessionist movement. After the state of Virginia passed the Articles of Secession on April 17, 1861, residents of the western part of the state voted to form their own pro-Union government, and West Virginia was officially recognized as a state by President Lincoln in 1863.

So it comes as no surprise that West Virginia’s hills and hollers have hidden illicit moonshine stills as long as it has been a state.

When I interviewed West Virginia House delegate Doug Smith about sponsoring the “moonshine bill” it was clear that he came at the issue more as an enthusiastic hobbyist than a champion of West Virginia history and heritage. Smith himself is originally from Kansas, with no family history of moonshining (that he knows of). But he does see the bill as an opportunity to reclaim a part of West Virginia’s history that has long been seen as shady or even shameful. In our conversation he said that he hoped passage of the bill would spur the creation of moonshine festivals where hobbyists could mingle with commercial distillers and visitors could taste a bit of West Virginia’s heritage.

As if on cue, the first annual West Virginia Moonshine Festival was announced one day before the new law was scheduled to go into effect on June 7, 2024. Incidentally, the festival was held in Harper’s Ferry, the site of another of the country’s most infamous acts of rebellion against the state—John Brown’s doomed raid on a federal armory, a failed attempt to arm an organized rebellion against slavery.

Moonshine has long been part of the state’s history of resistance, and the right to distill may be the next libertarian cause celebre. Smith, who describes himself as having “libertarian leanings when it comes to personal liberty” sees the federal ban as an unnecessary incursion on individual freedom. He says, “Personally, I believe the current federal ban on home distilling exceeds the scope of the Federal government’s limited powers”. The Texas federal court seems to agree.

With the court’s decision unchallenged, it falls to the states to decide how illegal moonshining will be. Several states already have statutes that default to the federal law, and presumably more will now follow.

So, what becomes of the deep history of moonshining as an act of rebellion? If home distilling is legal, is it still resistance? If it’s legal, is it still moonshine?

The answer is wrapped up in the complex role that moonshine plays in rural communities. As a matter of tradition, legalization will give home distillers a chance to practice their craft, to hone and pass on their knowledge to the next generation. This is a welcome relaxation of the notion that there is something inherently dangerous or nefarious about making your own whiskey that doesn’t apply to home-brewed beer or wine (both of which have long been legal).

Distilled spirits have always been treated differently under the law, with the rationale that the higher alcohol content makes distilled alcohol more dangerous than beer—both physically and morally.

But the burr under the government’s saddle hasn’t just been a puritanical aversion to intoxication on moral grounds. It has always been about money, and about control. While you might be able to make 10 gallons of booze a year in West Virginia, you definitely are not allowed to sell it. If moonshining is part of how you make ends meet, you either submit to the state’s regulatory bureaucracy, or you’re still a criminal.

Because just as liquor is an important economic resource for rural folks around the world, excise taxes on liquor are an important source of revenue for the state. But as Steven Stoll says in Ramp Hollow, taxation isn’t just about revenue—it’s a potent expression of the territorial power of the state. When you have something like liquor—which functions as a long-term store of value, a source of income, and in many cases as a form of currency in itself—it can undermine the reach of the state into the daily lives of rural folks.

It may seem like a big deal to reverse 150 years of established law on corn squeezins, but it’s really just bringing the US closer to how most other countries treat homemade liquor: you can distill at home as long as you aren’t trying to sell it. This, of course, denies the reality of how homemade liquor functions in rural communities. From Cocke County Tennessee where I did my master’s research with Smoky Mountain moonshiners, to Romania, India, and Brazil, the importance of home distilling as a cultural tradition and as an economic resource cannot be disentangled.

Under the new law, West Virginians who make a bit of liquor for fun will be fully legal hobby distillers. But if making liquor is part of how you make a living, you’ll still be a moonshiner.

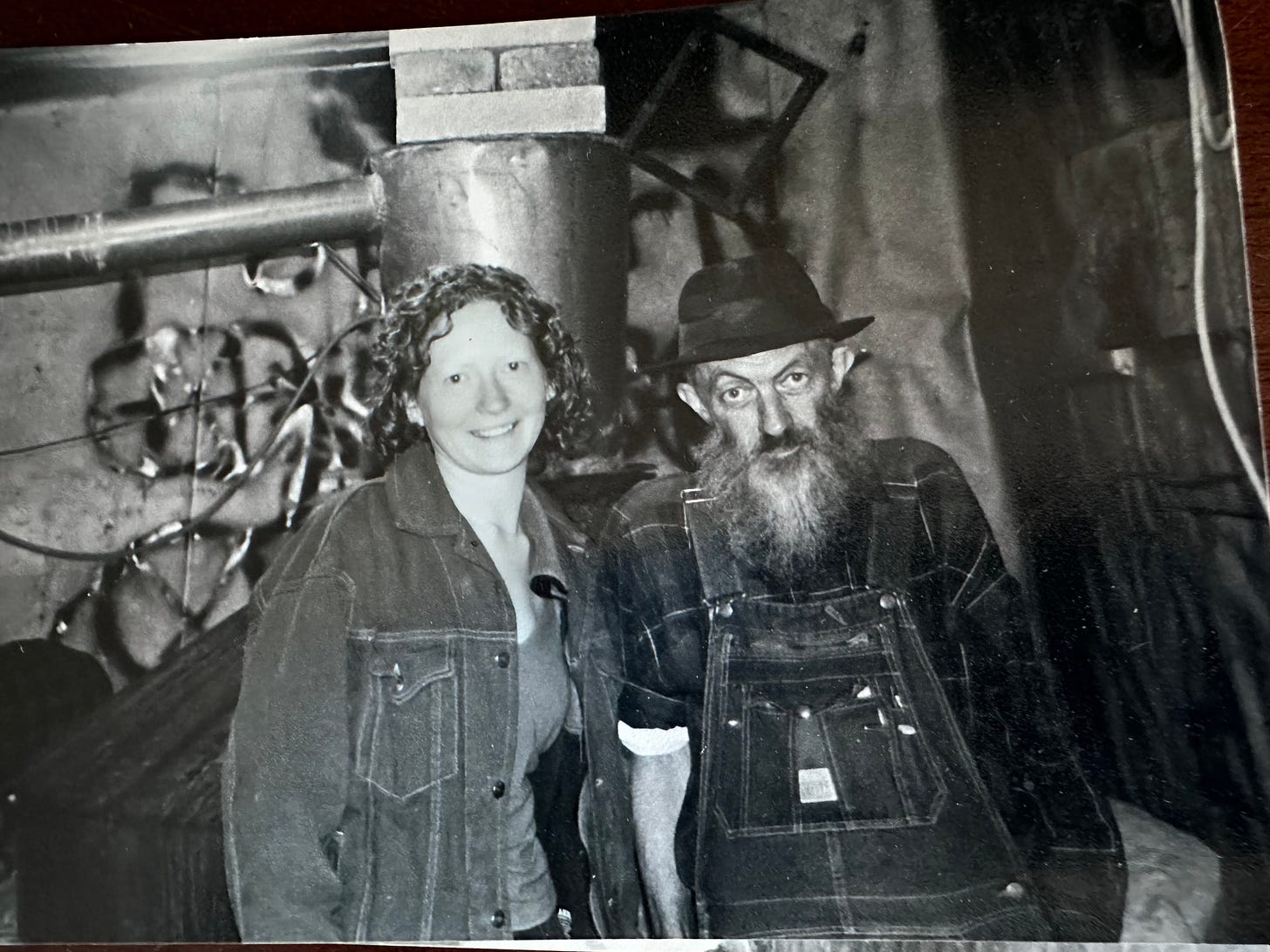

Cute pic with Popcorn... rather schizo decision that seems to sit with other such situations.

Last time I had Cocke Co moonshine (at a happy occasion) it was the smoothest alcohol I've ever tried. I don't remember anything else...

Your question, if it’s legal, is it still moonshine?, sounds a bit like a Zen koan…up here in the far NE corner of TN, moonshine has apparently become almost extinct. Have been unable to locate any for the past couple of years